Black History Month Spotlight: Jackie Robinson

02/10/2021

Black History Month is an annual celebration of the achievements by African Americans and a time for recognizing their role in U.S. history. For the second week in February 2021, we commemorate Major League Baseball legend and AAU alum Jackie Robinson.

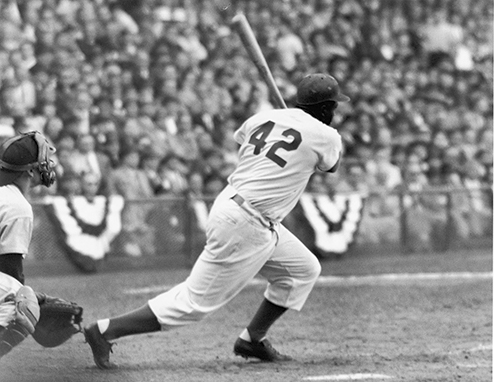

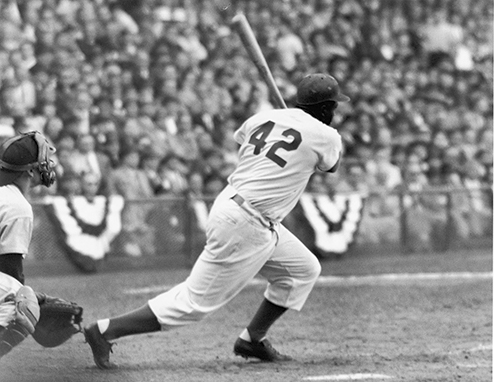

Jackie Robinson, born Jack Roosevelt Robinson, was more than just a baseball star, wearing the No. 42 on the field, he challenged the traditional basis of segregation that had in the 1940s marked most aspects of American life.

Robinson pushed the envelope and broke through the barrier on multiple fronts. Before his Major League Baseball years (MLB), he earned varsity letters all four years in football, basketball, track and baseball at Pasadena Junior College and at University of California - Los Angeles (UCLA).

“None of the great all-around athletes, from Jim Thorpe to Glenn Davis to Bo Jackson to Deion Sanders, have shown the ability at such a high level in so many sports,” said the Los Angeles Times.

Robinson’s older brothers Mack (himself an accomplished athlete and silver medalist at the 1936 Summer Olympics) and Frank inspired Robinson’s interest in sports. He went on to actually break his brother Mack’s broad jump records at Pasadena Junior College (PJC).

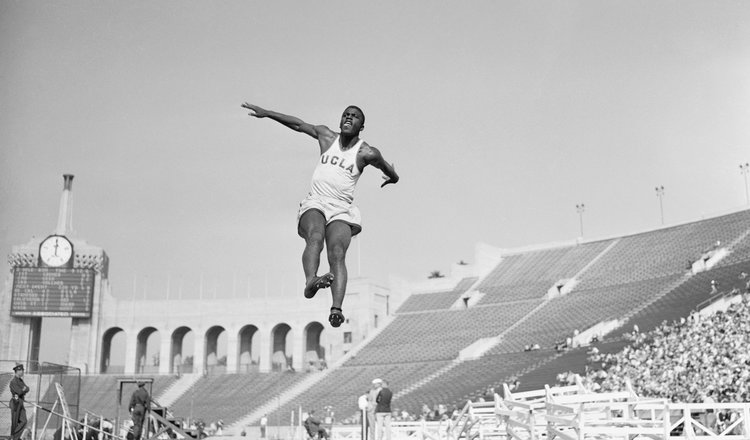

After graduating from PJC in the spring of 1939, Robinson enrolled at UCLA. There he was one of four African-American players on the Bruins’ 1939 football team that went undefeated with four ties, 6-0-4. Baseball was Robinson's "worst sport" at UCLA; he hit .097 in his only season, although in his first game he went 4-for-4 and twice stole home. In track and field, Robinson won the 1940 NCAA championship in the broad jump with a 7.58m (24’ 10.25”).

That same year, Robinson also competed in the 1940 AAU Track and Field Championship for the Southern California Athletic Association. His season best that year was a 7.62m (25’), the fourth best in the world, according to AAU findings. Robinson was a favored athlete to compete for the United States in the 1940 and 1944 Olympic Games, however the Games were cancelled due to World War II.

In early 1945, the Kansas City Monarchs, an African-American league sent Robinson a written offer to play for them. Robinson accepted and played well for the Monarchs, but was quickly frustrated by the disorganization of the league. Branch Rickey, club president and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, began to scout the African-American leagues for a possible addition to the Dodgers' roster.

Rickey took an interest in Robinson and on November 1, 1945, Robinson formally signed his contract with the feeder team of the Dodgers, the Montreal Royals.

In 1947, the Dodgers called Robinson up to the major leagues six days before the start of the season and on April 15, he made his major league debut before a crowd of 26,623.

In a year wrought with skepticism and racial tension, Robinson finished the season having played in 151 games for the Dodgers, with a batting average of .297, an on-base percentage of .383, and a .427 slugging percentage. He had 175 hits (scoring 125 runs) including 31 doubles, 5 triples, and 12 home runs, driving in 48 runs for the year. Robinson led the league in sacrifice hits, with 28, and in stolen bases, with 29. His cumulative performance earned him the inaugural Major League Baseball Rookie of the Year Award (separate National and American League Rookie of the Year honors were not awarded until 1949).

After a ten-year stint in the MLB, Robinson retired with several honors- All-Star for six consecutive seasons from 1949 through 1954 and the National League Most Valuable Player Award in 1949, the first African-American to do so. He played in six World Series and contributed to the Dodgers' 1955 World Series championship.

Robinson's major league debut brought an end to approximately sixty years of segregation in professional baseball, known as the baseball color line. After World War II, several other forces were also leading the country toward increased equality for African Americans, and President Harry Truman's desegregation of the military in 1948. Robinson's breaking of the baseball color line and his professional success symbolized these broader changes and demonstrated that the fight for equality was more than simply a political matter.

Civil rights movement leader Martin Luther King Jr. said that he was "a legend and a symbol in his own time", and that he "challenged the dark skies of intolerance and frustration." According to historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, Robinson's "efforts were a monumental step in the civil-rights revolution in America ... [His] accomplishments allowed black and white Americans to be more respectful and open to one another and more appreciative of everyone's abilities."

Post-baseball life for Robinson included many more firsts. In 1962, He became the first African American player to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

In 1965, Robinson served as an analyst for ABC's Major League Baseball Game of the Week telecasts, the first African American person to do so. In 1966, Robinson was hired as general manager for the short-lived Brooklyn Dodgers of the Continental Football League. In 1972, he served as a part-time commentator on Montreal Expos telecasts.

On June 4, 1972, the Dodgers retired his uniform number, 42, alongside those of Roy Campanella (39) and Sandy Koufax (32). From 1957 to 1964, Robinson was the vice president for personnel at Chock full o'Nuts; he was the first African American person to serve as vice president of a major American corporation. Robinson always considered his business career as advancing the cause of African American people in commerce and industry. Robinson also chaired the NAACP's million-dollar Freedom Fund Drive in 1957, and served on the organization's board until 1967. In 1964, he helped found, with Harlem businessman Dunbar McLaurin, Freedom National Bank—an African American-owned and operated commercial bank based in Harlem. He also served as the bank's first chairman of the board. In 1970, Robinson established the Jackie Robinson Construction Company to build housing for low-income families.

He made his final public appearance on October 15, 1972, throwing the ceremonial first pitch before Game 2 of the World Series at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati.

Nine days later on October 24, 1972, Robinson died of a heart attack at his home. He was 53 years old. Robinson's funeral service on October 27, 1972, at Upper Manhattan's Riverside Church in Morningside Heights, attracted 2,500 mourners. Many of his former teammates and other famous baseball players served as pallbearers.

In 1999, Robinson was named by Time on its list of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century. He ranked number 44 on the Sporting News list of Baseball's 100 Greatest Players and was elected to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team as the top vote-getter among second basemen. Robinson was among the 25 charter members of UCLA's Athletics Hall of Fame in 1984. Robinson has also been honored by the United States Postal Service on three separate postage stamps, in 1982, 1999, and 2000.

On April 15, 1997, Robinson's jersey number, 42, was retired throughout Major League Baseball, the first time any jersey number had been retired throughout one of the four major American sports leagues. In addition, the MLB in 2004 began honoring Robinson by allowing players to wear number 42 on April 15, Jackie Robinson Day.

Robinson pushed the envelope and broke through the barrier on multiple fronts. Before his Major League Baseball years (MLB), he earned varsity letters all four years in football, basketball, track and baseball at Pasadena Junior College and at University of California - Los Angeles (UCLA).

“None of the great all-around athletes, from Jim Thorpe to Glenn Davis to Bo Jackson to Deion Sanders, have shown the ability at such a high level in so many sports,” said the Los Angeles Times.

Robinson’s older brothers Mack (himself an accomplished athlete and silver medalist at the 1936 Summer Olympics) and Frank inspired Robinson’s interest in sports. He went on to actually break his brother Mack’s broad jump records at Pasadena Junior College (PJC).

After graduating from PJC in the spring of 1939, Robinson enrolled at UCLA. There he was one of four African-American players on the Bruins’ 1939 football team that went undefeated with four ties, 6-0-4. Baseball was Robinson's "worst sport" at UCLA; he hit .097 in his only season, although in his first game he went 4-for-4 and twice stole home. In track and field, Robinson won the 1940 NCAA championship in the broad jump with a 7.58m (24’ 10.25”).

That same year, Robinson also competed in the 1940 AAU Track and Field Championship for the Southern California Athletic Association. His season best that year was a 7.62m (25’), the fourth best in the world, according to AAU findings. Robinson was a favored athlete to compete for the United States in the 1940 and 1944 Olympic Games, however the Games were cancelled due to World War II.

In early 1945, the Kansas City Monarchs, an African-American league sent Robinson a written offer to play for them. Robinson accepted and played well for the Monarchs, but was quickly frustrated by the disorganization of the league. Branch Rickey, club president and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, began to scout the African-American leagues for a possible addition to the Dodgers' roster.

Rickey took an interest in Robinson and on November 1, 1945, Robinson formally signed his contract with the feeder team of the Dodgers, the Montreal Royals.

In 1947, the Dodgers called Robinson up to the major leagues six days before the start of the season and on April 15, he made his major league debut before a crowd of 26,623.

In a year wrought with skepticism and racial tension, Robinson finished the season having played in 151 games for the Dodgers, with a batting average of .297, an on-base percentage of .383, and a .427 slugging percentage. He had 175 hits (scoring 125 runs) including 31 doubles, 5 triples, and 12 home runs, driving in 48 runs for the year. Robinson led the league in sacrifice hits, with 28, and in stolen bases, with 29. His cumulative performance earned him the inaugural Major League Baseball Rookie of the Year Award (separate National and American League Rookie of the Year honors were not awarded until 1949).

After a ten-year stint in the MLB, Robinson retired with several honors- All-Star for six consecutive seasons from 1949 through 1954 and the National League Most Valuable Player Award in 1949, the first African-American to do so. He played in six World Series and contributed to the Dodgers' 1955 World Series championship.

Robinson's major league debut brought an end to approximately sixty years of segregation in professional baseball, known as the baseball color line. After World War II, several other forces were also leading the country toward increased equality for African Americans, and President Harry Truman's desegregation of the military in 1948. Robinson's breaking of the baseball color line and his professional success symbolized these broader changes and demonstrated that the fight for equality was more than simply a political matter.

Civil rights movement leader Martin Luther King Jr. said that he was "a legend and a symbol in his own time", and that he "challenged the dark skies of intolerance and frustration." According to historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, Robinson's "efforts were a monumental step in the civil-rights revolution in America ... [His] accomplishments allowed black and white Americans to be more respectful and open to one another and more appreciative of everyone's abilities."

Post-baseball life for Robinson included many more firsts. In 1962, He became the first African American player to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

In 1965, Robinson served as an analyst for ABC's Major League Baseball Game of the Week telecasts, the first African American person to do so. In 1966, Robinson was hired as general manager for the short-lived Brooklyn Dodgers of the Continental Football League. In 1972, he served as a part-time commentator on Montreal Expos telecasts.

On June 4, 1972, the Dodgers retired his uniform number, 42, alongside those of Roy Campanella (39) and Sandy Koufax (32). From 1957 to 1964, Robinson was the vice president for personnel at Chock full o'Nuts; he was the first African American person to serve as vice president of a major American corporation. Robinson always considered his business career as advancing the cause of African American people in commerce and industry. Robinson also chaired the NAACP's million-dollar Freedom Fund Drive in 1957, and served on the organization's board until 1967. In 1964, he helped found, with Harlem businessman Dunbar McLaurin, Freedom National Bank—an African American-owned and operated commercial bank based in Harlem. He also served as the bank's first chairman of the board. In 1970, Robinson established the Jackie Robinson Construction Company to build housing for low-income families.

He made his final public appearance on October 15, 1972, throwing the ceremonial first pitch before Game 2 of the World Series at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati.

Nine days later on October 24, 1972, Robinson died of a heart attack at his home. He was 53 years old. Robinson's funeral service on October 27, 1972, at Upper Manhattan's Riverside Church in Morningside Heights, attracted 2,500 mourners. Many of his former teammates and other famous baseball players served as pallbearers.

In 1999, Robinson was named by Time on its list of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century. He ranked number 44 on the Sporting News list of Baseball's 100 Greatest Players and was elected to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team as the top vote-getter among second basemen. Robinson was among the 25 charter members of UCLA's Athletics Hall of Fame in 1984. Robinson has also been honored by the United States Postal Service on three separate postage stamps, in 1982, 1999, and 2000.

On April 15, 1997, Robinson's jersey number, 42, was retired throughout Major League Baseball, the first time any jersey number had been retired throughout one of the four major American sports leagues. In addition, the MLB in 2004 began honoring Robinson by allowing players to wear number 42 on April 15, Jackie Robinson Day.

Email

Email Print

Print